Isshinryu

While Isshin-ryu is a relatively new style, and while it has been fairly controversial since its establishment in 1954, it is important to realize that Isshin-ryu is very firmly rooted in traditional karate, and that, while Master Shimabuku was an innovator, he was also the most accomplished traditionalist of his day. Thus Master Shimabuku may be likened to other great and innovative artists, such as architect Frank Lloyd Wright or the painter, Picasso. While Wright introduced many new and bold concepts to the art of building, and in some ways revolutionized the practices of architecture, he was well trained in principles, techniques and materials that go back to the builders of ancient civilizations. And while Picasso’s paintings reflect his radical departure from traditional depiction of images, he was able to paint as realistically as any landscape or portrait artist. No one lacking the formal training of these two figures could have possibly matched their innovative creativity. Similarly, Isshin-ryu could have been invented only by one who had absolutely mastered traditional karate. Tatsuo Shimabuku was an acknowledged expert in Goju-ryu and Shorin-ryu before he refined and tempered the techniques, and handed down a style that is as pure and effective as any practiced today.

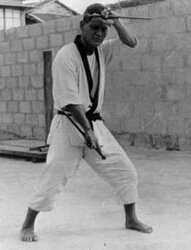

Master Shimabuku

Master Shimabuku

Performing Sai

Master Shimabuku was born on September 19,1908, and began his study of karate as a boy with his uncle, who practiced Shuri-te. He continued his studies with three great Okinawan masters: Chotoku Kyan, Chojun Miyagi and Choki Motobu. These three are featured in “The Weaponless Warriors”; and Richard Kim’s notes and charts clearly show how they tie into the long tradition of karate. Kyan was a student of Master Yasutune Itosu, who taught Shuri-te, and of, Master Matsumora, who taught Tomari-te. These two styles were combined to form Shorin-ryu (named after the Shaolin Temple tradition), and Kyan was one of Shorin-ryu’s greatest practitioners. He was famous for his powerful kicks and for his outstanding teaching ability. Kyan was a stern perfectionist, and young Tatsuo Shimabuku achieved the honor of being his best student.

Miyagi (1888-1953) was the best student of the Naha-te grandmaster, Kanryo Higashionna (1845-1915). Higashionna had established Naha-te by combining te with Chinese kempo, which he had studied for years in China. Naha-te was distinguished by its integration of soft kempo and hard kempo. It emphasized the Sanchin stance, which Higashionna had developed to the point that he was immovable when he had assumed the stance and heated the floor with the powerful gripping of his toes. Miyagi studied with Higashionna for a number of years then went to China himself to study kempo. He returned to Okinawa and formulated the style called Goju-ryu (hard/soft way). For accounts of his deeply respected personality and his lifelong devotion to and techniques in karate, consult the chapters on Miyagi by Richard Kim and Frank Van Lenten. Miyagi was known as an exacting sensei whose grueling workouts greatly strengthened the body and built up endurance. With Miyagi, Tatsuo Shimabuku went through training that was very influential to the ultimate development of Isshin-ryu; for example, the emphasis on breathing and tension, the low kicks, and the development of mind, body and spirit. Motobu was a less formal instructor, but an accomplished master in Shorin-ryu, and an indomitable fighter. Coming from an ancient line of Okinawan nobles, he had an eccentric personality and an enormous physique. As Richard Kim states, he is remembered as a brawler as well as a master, but no doubt his instruction offered Tatsuo Shimabuku invaluable lessons on the practical application of the art of karate.

Master Shimabuku

Pounding nails with his hand

The Mizugami Patch

Under these three sensei’s, Tatsuo Shimabuku developed abilities that mutually complemented one another in making him a quintessential karate-ka; flexibility, coordination, power, speed, balance, ki, technical perfectionism, oneness with the art, heightened awareness, honor, humility, streetwise practicality. With additional training under weapons experts, Tatsuo Shimabuku became one of the most accomplished karate-ka of his day. From the late 1920’s to the 1940’s, Master Shimabuku’s prestige and authority in karate increased. Like most of the Okinawan population, Master Shimabuku was a poor farmer. He also worked in his village as a local tax collector. The first half of the 20th century was very difficult for Okinawans in his station in life. The Japanese rulers were unconcerned about the extreme economic hardship on the island, and unresponsive to the Okinawan leaders’ petitions for land and tax reform.

Karate was Master Shimabuku’s way of life, but at that time the art would not earn a living for most of its experts. With the advent of World War II and the forced conscription of thousands of Okinawan men, Master Shimabuku and his family sought refuge on another island. Shortly before the Japanese surrender, the Battle of Okinawa devastated the island, its economy and its inhabitants. The Japanese stubbornly resisted the Allied Forces from its headquarters in the ancient castle at Shuri. The Americans dropped tons of explosives on the island and waged bloody infantry tactics. Most of the ancient buildings, gardens and monuments of the ancient Ryukyuan kingdom were destroyed, and over 100,000 civilians were killed (along with an additional 100,000 soldiers). After the Japanese were defeated, the Americans occupied Okinawa and began a massive effort of reconstruction. Having returned to Okinawa, Master Shimabuku resumed farming, until Okinawan civilians and, later, American servicemen began to seek him out for instruction in karate. In the early 1950’s, Master Shimabuku decided to establish a formal dojo at his home in Chun Village, and became one of the first successfully professional sensei’s. Later, the school’s success prompted Master Shimabuku to move his dojo to Agena, where large numbers of Americans could have access to his instruction.

Master Shimabuku had been experimenting with new approaches in karate for a long time. But with his energies focused on his art, Master Shimabuku’s creative spirit increasingly analyzed and synthesized all the kata, techniques and applications he had perfected. He continued the slow, methodical, thorough process of modifying Shorin-ryu and Goju-ryu into a style that he found more practical and effective. His experimentation was galvanized by his visionary dream of the Mizu-Gami. ( Master Arsinio J. Advincula, who spent many years studying in Master Shimabuku’s dojo is credited with designing the Isshin-ryu patch). The vision unified his ideas and his purpose. On January 15, 1956, Master Shimabuku publicly proclaimed that he would teach a new style called Isshin-ryu, one heart or whole-hearted way.

Master Shimabuku always said that there was “no birthday” for Isshin-ryu. He had been adding to, and subtracting from the style for years before 1959. His aim has been to develop a system that would apply sudden, direct, powerful force, while eliminating unnecessary movement. His ideas and innovations in karate are preserved in, and handed down through, the eight empty-hand kata of Isshin-ryu: Seisan, Seiuchin, Naihanchi, Wansu, Chinto, Kusan Ku, Sunsu and Sanchin. Most of these katas were adapted from their ancient forms, while Sunsu (or Sunusu, “son of Su (the ancestral house of Shimabuku)” was created by Master Shimabuku and, therefore, embodies Isshin-ryu in its essence. These katas were chosen, and refined laboriously and assiduously so that they might exemplify Isshin-ryu, and aid in the instruction of students in Isshin-ryu. They are a legacy from Master Shimabuku that continues to be handed down from sensei to student. For almost twenty years, Master Shimabuku taught Isshin-ryu to many Americans, as well as Okinawans. But his style was not readily accepted by the traditionalist karate-ka. Unfortunately, there is no completely reliable publication in print on the history of Isshin-ryu. Master Tatsuo Shimabuku died May 30, 1975. Before his death, he was filmed performing the Isshin-ryu kata on at least two occasions. While Isshin-ryu has suffered a decline in Okinawa, in America the style is thriving, owing largely to the dedication of Master Shimabuku’s students, who have established their own dojo’s all over the nation, and have endeavored to pass on Isshin-ryu in its prescribed form. We have seen what a unique and phenomenal creation Isshin-ryu karate is. Master Shimabuku never dwelt on the past, but lived squarely in the present. The future of Isshin-ryu is in the hands of the present. Today’s Isshin-ryu karate-ka should strive to preserve such a singular creation in its original form, through cooperation, careful study, and a new area of tradition. * Reference the American Okinawan Karate Association